Citrus spp.

Citrus

Origin

The origin and taxonomy are disputed because of the many interspecific hybrids, the frequency of bud mutations and cultivation and dispersal over millennia. However, most species are thought to come from the broader Southeast Asian region. The major types grown worldwide are: sweet oranges (68%), mandarins and their hybrids (19%), lemon and lime (8%) and grapefruit and pummelo (4%). Examples of other minor citrus species and their close variants are calamondin, citron, ethrog, Kaffir lime, rough lemon, desert lime, kumquat, microcitrus (which includes the finger lime) and trifoliate orange. There are also novelty citrus such as blood orange and Buddha’s hand.

Climate

There are variations between species but generally preferred precipitation and temperatures are about 1000mm pa and 12-37°C, with a winter dormancy period of 1-10°C to stimulate the switch from vegetative to reproductive growth. Mature trees can tolerate some light frost but fruit is damaged. They can not withstand temperatures approaching 50°C. In tropical climates, with no cool winter, the fruit skin colour stays green when ripe. Humidity also affects the characteristics of the fruit.

Plant Description

Small to medium evergreen trees, 2-15m high depending on species, often with thorny shoots. The alternate leaves are lanceolate to roundish and 4-10cm long depending on species. Some have winged petioles.

Relatives

Rutaceae Family, which includes white sapote, curry leaf, wampi and bael fruit.

Soils

A wide range of soil types is tolerated if well-drained. The ideal is for them to be fertile sandy loams, well-aerated and with pH 6-6.5. Higher pH will cause trace element deficiencies. There is little tolerance of saline soils.

Propagation

Seeds in citrus are of 2 types, zygotic and nucellar. The former will not come true to type and juvenility is extended; the latter will be clones of the maternal plant but are still mainly used only as rootstocks rather than as fruiting trees. The almost universal technique is budding. Top working of mature trees by budding is also practiced when there is declining productivity or a better cv is required; this will usually enable faster return to fruiting than removal and starting anew. Rootstock selection is very important and species specific.

Cultivars

Many, including special rootstock cultivars addressing particular features such as: dwarfing, tree vigour, yield, fruit size, uptake of water and nutrients, holding quality on the tree, cold tolerance and ability to provide resistance to various diseases and pests.

Flowering and Pollination

The often strongly scented white or pinkish flowers are solitary or in small corymbs, 2–4 cm diameter, with usually 5 white petals, numerous stamens, an 8-15 cell ovary and a style with as many partitions as there are cells in the ovary. Most cultivars are self-pollinated and do not require cross pollination, but some are essentially sterile (pollen and or ovule) and some set fruit parthenocarpically. Hundreds of flowers are typically produced in spring but only 1-2% of these may result in mature fruit. There is usually an initial fruit drop and then another pre-harvest dependent on prevailing conditions. Bees and other insects are the usual pollinators.

Cultivation

Choose a location in full sun. Enrich the soil with mature compost and manure before planting. Citrus trees are shallow rooted, so surface competition (such as in lawns) should be avoided. The objective with young trees is to maximise vegetative growth to bring the plant into fruiting as soon as possible; fertilizer is applied 4-6 times/yr and plants should be kept well-watered. With mature plants fertilizer is split into 2-3 applications. Micronutrient deficiencies are usually addressed by foliar sprays. With producing plants, water stress will reduce growth, yield and fruit quality, but overwatering will lead to excessive vegetative growth. Fruit should not be allowed to develop until the tree is mature. Mulching is beneficial.

Wind Tolerance

Good.

Pruning

Pruning is not necessary to produce fruit, but may be used to shape the tree and allow sunlight in. A gentle pruning while harvesting is best: fruits are often borne on the tips of branches. Clip the fruit plus stem back to the nearest new shoot on the same branch. This stimulates the growth of more branches with new tips. Remove dead twigs and branches.

The Fruit

The fruit is a hesperidium, a specialised berry, globose to elongated with a leathery rind. The outer layer of the rind (the ‘zest’) is bitter and commonly contains small pockets of aromatic oils. The fruit pulp is in segments filled with fragrant juice vesicles. The juice contains a high quantity of citric acid giving the characteristic sharp flavour, with a sugar/acid ratio of around 12:1 favoured by most people. Nutritional qualities include vitamins A and C; carbohydrate content is about 12%.

Fruit Production and Harvesting

Citrus typically ripen in late autumn or winter. Skin colour is a poor indicator of maturity and mainly a reflection of climate. In tropical climates, with no cool winter, the fruit skin colour stays green when ripe. Humidity also affects the characteristics of the fruit. Fruit are non-climacteric so should be picked when fully ripe. Fruit in some cvs ‘store’ well on the tree. Clip the fruit from the stem so as not to tear the skin; this is particularly the case for some mandarin cvs.

Fruit Uses

Most citrus are eaten fresh or used in juices. They are also preserved in jams, marmalades or pickles. The rind is often used to add ‘zing’ to processed foods and the leaves of kaffir lime are used for flavouring many Asian dishes. Storage period for citrus is much better than for many fruit, often up to 3-4 months at 2-4°C.

Pests and Diseases

There are many possible, but these can be minimised if trees are well-managed and located in a sunny position. Spraying with pest oil controls scale insects and aphids. Psyllids can carry fatal citrus diseases. Medfly can be a serious problem, particularly with mandarins and oranges: set out appropriate baits and practice orchard sanitation by removing all infested and fallen fruit for proper disposal. Citrus leaf miner is a major problem with young trees and maturing leaves. The biggest problems in commercial production are caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses and mycoplasmas. Parrots also will attack citrus fruit.

Comments

Citrus trees are stars in our gardens. Many of them also do well in pots.

More Information

Citrus Names and Varieties

Have you ever tried to understand the naming and relationships of the numerous Citrus varieties available? It’s not simple (some would say it’s chaotic!) because of the usual problems with common & varietal names that can differ greatly round the world and can be assigned for all sorts of non-botanical reasons, and even with binomials it can be confusing because species in the genus hybridise so readily and some hybrids are incorrectly named as individual species. For example globally, sweet orange is the most commonly grown Citrus and is frequently referred to as C sinensis, but it’s actually a complicated hybrid that was naturally formed from other progenitor species and introgressions eons ago, and further hybridisation has continued through to the present day with domestication and breeding. The binomial is not officially accepted.

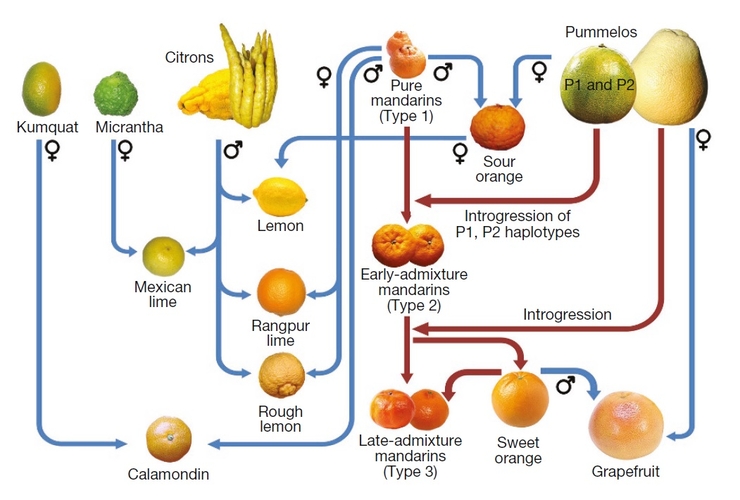

A very thorough study published in Nature (GA Wu et al, (2018), 554, 311-316) has addressed the genomics and evolution of ten commonly known citrus types using genomic, phylogenetic and biogeographic analyses of 58 accessions representing diverse Citrus germplasms. Their data suggest the genus originated in south east Asia and began to diversify through the late Miocene (11-5 million years ago), with variously admixed genomes leading to the major commercial types we’re familiar with. They found evidence of an extensive network of relatedness between mandarins and sweet oranges, indicating the role domestication has played with these two major crops. The picture summarises their findings.

At the top, the three pivotal progenitor species are shown – citron (C medica), mandarin (C reticulata) and pummelo (C maxima, with 2 haplotypes P1 and P2); the other two species playing lesser roles are nagami kumquat (Fortunella margarita) and C micrantha. For those not familiar with biology, the small black circles with an arrow or cross indicate males and females respectively involved in sexual reproduction. The blue lines with arrows show the direction of simple crosses between male and female parents, forming for example calamondin and Mexican lime. Lemons are derived from a male citron and female sour orange, which itself was formed from a mandarin pummelo cross. Type 2 mandarins are formed by a cross of pummelos and pure (type 1) mandarins, and these have variously crossed again with pummelos to produce sweet oranges. Somatic mutations (sports) of a common genome then underlie many modern sweet orange cultivars. As an example of the genetic content in mandarin pummelo crosses, type-2 and 3 mandarins have 1-10 and 12-38% pummelo genes respectively. The authors suggested that with the initial cross of mandarin and pummelo to produce type 2 mandarins, mandarin genes were successively diluted by repeated mandarin backcrosses. Pummelo parentage has played a major role in fruit size and acidity. For example regarding size, mandarins with an average fruit diameter of 4-7cm had pummelo genetic content of 5-20%, sweet oranges of 7-8cm dia had 45-50%, and grapefruit of 9-12cm had 60-65%. There was a similar effect with acidity, eg sour orange being more acid than type-1 mandarins. The study confirmed the appropriateness of Fortunella margarita now belonging in the Citrus clade (as C japonica); C micrantha is also now classed as a synonym of C hystrix.